Hector Berlioz: Bearer of Romanticism’s Torch: Part I

I’ve said a bit about Hector Berlioz now and then since I’ve been writing here. But in this and the next entry I hope to put my Berliozian thoughts together, to offer you the Big Picture as well as the details. Berlioz might actually be the high-point of romanticism. He believed, and his admirers echo him here, that he had taken up music at the point to which Beethoven had carried it, and continued its progress. Brian Primmer has written, “His harmonic progressions showed how the grammar of music could be refashioned.”

I’ll write today specifically about the five operas attributed to this great Romantic. I’ll take them up in chronological order.

1. Les francs-juges (1826).

This opera, “The free judges,” is for the most part lost to us. Berlioz, still in his early twenties, composed to a libretto by his friend Humbert Ferrand. But the intended theatre, the Odéon, couldn’t get government permission for a staging.

Berlioz’ admirers have often blamed Ferrand’s libretto for this. One musicologist sums it up by saying that the cloudy and convoluted language “repeatedly befogs the purpose of the words.”

The opera went on a shelf, and at some later point Berlioz, blaming himself rather than his friend, destroyed most of the score. Some fragments remain, among them the overture, to which you can listen here. With due respect, it does sound a bit in parts like Berlioz may have been a young man too determined to seem mature and sententious.

Nonetheless, Franz Liszt, no less, was impressed, and in time created a piano transcription of this overture.

Berlioz’ second opera, or the first that survives in full, is

2. Benvenuto Cellini (1838).

This one, which takes its name from a Florentine sculptor of the 16th century, famously set off a riot in the streets of Paris, so different – so odd – seemed the style.

This one, which takes its name from a Florentine sculptor of the 16th century, famously set off a riot in the streets of Paris, so different – so odd – seemed the style.

Cellini himself must have seemed a promising subject. His works include “Perseus with the Head of Medusa,” a remarkable statute (photo on the left) that you may find in the Loggia del Lonzi.

Yet Cellini is perhaps better remembered for his colorful life and his boastful autobiography than for the body of his work.

Berlioz’ opera is a comic reworking of Cellini’s own account of how he came to create the Perseus.

The problem wasn’t with the story, though. It was Berlioz’ still-developing musical style. Not only did it provoke much of the audience into violent reactions, it annoyed some of the performers, too. Gilbert Duprez, the tenor with the title role, found the music too demanding of stamina, too idiosyncratic in tessitura. In his own memoir, written many years later, Duprez would say that Berlioz’ talent “n’était pas précisément mélodique” (was not precisely melodic.)

Here posterity takes Berlioz’ side: Duprez’ precision was another man’s prison!

A fascinating sidebar has come down to us: Cellini opened at a time when Duprez’s wife was heavy with child. She went into labor as he was leaving their home for the third performance. During the final act, Duprez saw a doctor – the doctor – standing in the wings, presumably with news. He was rattled and never for the remainder of that performance quite regained his stride.

[The newborn was a healthy boy.]

One consequence of Benvenuto, and all the attendant drama, for Berlioz’ career was that he received his first sustained notice on the other side of the Channel. London’s Musical World ran a long article on it.

3. La damnation de Faust (1846)

But in the way of all rebels, Berlioz aged, and his audience aged with him. Both became respectable with time. By the time he took on the topic of a deal-for-damnation, Berlioz was famous as a conductor and as the author of a very influential treatise on instrumentation.

As for this next work, Berlioz’ take on Faust, you’ll find it generally listed as a “concert drama” rather than an opera. But I’m including it with his operas, and I’m in good company there. Well-known filmmaker Terry Gilliam (famed for Brazil and Time Bandits as well as for his years in the Monty Python troupe), directed a performance of Berlioz’s Damnation at the English National Opera, in London, in 2011, treating it very much as an opera. Reviewer Rupert Christiansen, writing in The Telegraph, gave it his highest rating, five stars.

Christiansen praised “Edward Gardner’s magnificent conducting, Peter Hoare’s charismatic performance in the title role, Christopher Purves’ gloriously sardonic Mephistopheles [and] Christine Rice’s heartrending singing of Marguerite’s two gorgeous arias.”

That’s a lot to like.

But since this is www.justsheetmusic.com and our focus here is as ever on the music, we’ll offer you a link to one of those gorgeous arias, Marguerite’s D’Amour L’Ardente Flamme. It is sung in that clip by Vesselina Kasarova, a Bulgarian mezzo soprano better known for work in the Mozartian canon. I’ve put a photo of Kasarova at the top of this blog entry.

That aria shows how Berlioz pioneered the use of vocal timbre as a deliberate element in the structuring of a work.

It also shows the determined way in which the music expresses character, as does, to take another example, the starting-and-stopping fugue of Faust’s monologue at the start of Part II, where Faust has been driven to the brink of suicide by his own world-weariness.

It also shows the determined way in which the music expresses character, as does, to take another example, the starting-and-stopping fugue of Faust’s monologue at the start of Part II, where Faust has been driven to the brink of suicide by his own world-weariness.

4. Les Troyens (1858)

Les Troyens was, also, a distinctive take on a very traditional operatic theme. The theme is the aftermath of the fall of Troy, and most especially the arrival of Aeneas and his band of Trojans on the shores of North Africa, where Aeneas had his notorious fling with Queen Dido.

Between Acts III and IV there is a symphonic interlude known as “Royal Hunt and Storm.”

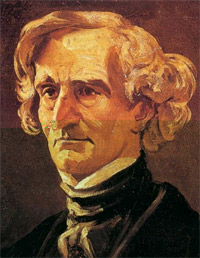

Hector Berlioz

Much of this is unabashed nature painting. Berlioz wants us to see the hunt, and then catch the scent and the windy force of the oncoming storm.

5. Béatrice et Bénédict (1862)

Berlioz’ final opera. Béatrice et Bénédict came about because Berlioz was fascinated by Shakespeare – a common enough fascination amongst the romantics. He has re-worked Shakespeare’s comedy Much Ado About Nothing, (a story with two central couples), so that one of those couples, Claudio and Hero, nearly disappears, and the whole “ado” turns out to be about Berlioz’ title characters.

In this case, as in Les Troyens, Berlioz wrote the libretto as well as composing its musical setting.

Throughout all of this, throughout what Berlioz himself called his long war “against the professors, the routineers, and the deaf,” there was a growth of confidence (he no longer thought he had to rely on someone else for the words) as well as constant invention, a constant pressing against expectation, and thus an expansion of what music could do and mean.

Let us conclude – until we meet again – with a concert hall recording of the Overture.

Go to: Hector Berlioz: Bearer of Romanticism’s Torch: Part II